|

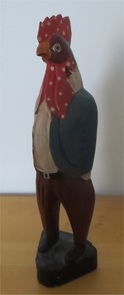

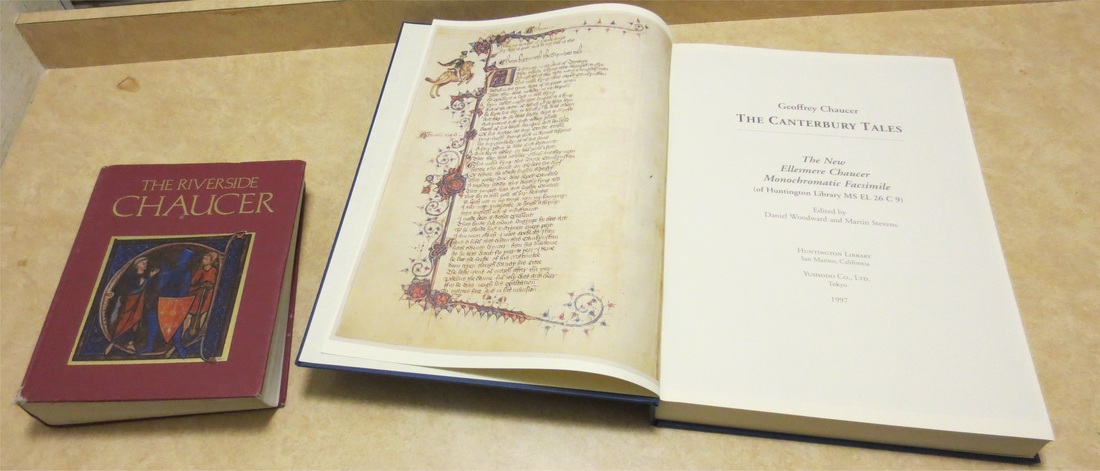

First off, I apologize for the complete lack of blog activity since the dramatic launch of this website last year. Due to my prodigious Web 2.0 savvy, I know that the best way to build an online audience is consistency, consistency probably even before quality of content. So, in pursuit of that goal, I've been consistently not posting anything new on the blog for the past five months. But, in all earnestness, I will do my best to reboot the original plan for substantive new posts every two weeks or so.  On to our subject for today: I've been having fantastic fun teaching my own Middle English course for the first time, and I thought I'd share some of the visual and aural aids I've found useful in introducing students to what can be intimidating and seemingly remote subject matter. Now, since prop comedy is generally regarded to be the lowest form of stand-up, I suppose it follows that "prop pedagogy" is also the lowest form of teaching. But I've long been a believer in the pedagogical efficacy of props, ever since I had the opportunity to lead a lecture on Chaucer's "Nun's Priest's Tale" for a Brit Lit survey, and decided on a whim to use this anthropomorphic rooster figurine to underline the comic potential of the beast fable genre. Not only does this gentlemanly cock cut quite the fine figure in his jacket and trousers, I find that it usefully embodies many of the comic tensions driving the poem, for example helping to bring out the subtle humor in passages like Pertelote's chiding, "How dorste ye seyn, for shame, unto youre love / That any thyng myghte make yow aferd? / Have ye no mannes herte, and han a berd?" (2918-2920). Well, no, Chaunticleer, in spite of his many virtues, unfortunately lacks a "mannes herte": he has a rooster's heart, something we can forget because of the poem's pervasive anthropomorphism.  But that was years ago and now I've got much more than a rooster statue up my sleeve. Let's begin with what I consider my real stroke of genius: a way to make the ubiquitous medieval trope of Fortune's Wheel a presence constantly felt in our very own classroom. It also provides an elegant solution to a certain practical problem, as you'll see. The course I'm currently teaching, "Dreaming and the Middle Ages," devotes the first half of the semester to Chaucer's dream visions and longer historical romance Troilus and Criseyde. Although my students are, for the most part, upper-level Notre Dame English majors, none of them had had prior experience with Middle English, which means I've had to emphasize the language component of the course. We almost always take some class time to translate a few stanzas together here and there, and it quickly became apparent that only a handful of students were ever going to be willing to volunteer. Since I dislike the apparent arbitrariness and adversarial student-teacher relationship that mere cold calling can evoke, I knew I needed to come up with a better way to get all of the students translating in class. Now, I knew from my own undergraduate Latin courses that, if one simply goes around the table in order, students tend to calculate which passage will fall to them and then work to translate it to perfection, ceasing to pay much or any attention to how their classmates are translating all of the intervening passages -- with terrible results for actual language learning. One of my Latin professors opted for the solution of writing our names on index cards and drawing from the freshly shuffled stack each day, but the pedagogical muse gifted me with an even better idea: why not let Lady Fortune herself -- the implacable blind goddess who rules the sublunary world, foe to Chaucer's bereaved Man in Black, the lovelorn Troilus, and the imprisoned philosopher Boethius alike -- determine who will translate next in class? All medievalists are familiar with the image of the Wheel of Fortune that adorns many a manuscript page as well as several of the covers of modern editions of certain medieval texts. For example, see this image from the first folio of British Library, MS Royal 20 C IV, which contains a French translation of Boccaccio's De casibus virorum illustrium (On the Fates of Famous Men), itself an influential model for an entire genre of writing chronicling the downfalls of great men, including Chaucer's own "Monk's Tale." As Fortune spins her wheel, she elevates some men from a lowly state to greatness, but also causes others already in prosperity and lofty positions to tumble down -- sometimes on multiple occasions in one lifetime. I'm especially fond of this particular illumination because of the way the artist depicts the unfortunate souls on the wrong side of the wheel physically tumbling out of their now upturned chairs.  Combine this hugely important image, which Chaucer repeatedly invokes in his poetry, with a modern carnival wheel, and what do you get? A perfectly fair because perfectly unfair and arbitrary way to choose the next student to translate! As you can see, I've simply keyed this inexpensive dry-erase carnival wheel to the students' initials, and one can never know where Fortune will choose to stop next. As I suggested earlier, this isn't a gimmick -- or, at least, not entirely a gimmick -- as it really does help the students appreciate the cruelty of Fortune and her terrifyingly arbitrary wheel through living it themselves. On the first day we used the wheel, I even made a student translate a second time when her name came up twice, because that's Fortune, right? The next day I admitted to some guilt over that, and excused her from translating the next time the wheel stopped on her name, and excused anyone else from having to translate twice on one day, in spite of the wheel: as I told them, "Fortune is cruel, but I am merciful."  I teach Chaucer's infamously enigmatic dream vision The House of Fame as above all a poem of images, or really of the full sensorium, with sight and sound emphasized although sometimes confused with one another, as when the human discourses that float up to the House of Fame again become embodied as their speakers. This next prop, then, is as much an aural aid as it is a visual one. If you recall, Chaucer depicts the mechanism by which fame both good and bad is spread across the world as a horn blown by the god of winds, Aeolus, and borne by his henchman Triton; one horn creates good fame, named "Clere Laude," and another black trumpet called "Sklaundre" spreads ill fame. Triton, of course, is the classical sea god that appears as an object of desire along with his most famous attribute, the horn, in Wordsworth's famous sonnet: "...Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn." While Chaucer does not make it clear that we should picture "Clere Laude" as the conventional conch shell of Triton's iconography, I like to think that it is, and I can attest that blowing a good long blast on a conch again helps make the sometimes distant images in these poems very immediate. For instance, the arresting image AND sound of someone blowing on a conch horn makes for a useful prologue to discussing the current of near synesthesia in The House of Fame, which reaches its high point in the description of the "blake trumpe of bras" Sklaundre. The sound of bad fame is first reified as a physical object, a cannonball (1643-1644), and then accompanied by a dark but multicolored smoke that both defies the laws of physics and offends the nostrils: "And hyt stank as the pit of helle" (1654). By the way, I happen to teach on the 7th floor of our library, the exclusive territory of Notre Dame's internationally renowned Medieval Institute, whereas I'm just a humble member of the humble English department myself -- I hope the conch hasn't earned me too much "bad fame" among the MI crowd.  The props are somewhat less flashy from here on out, and definitely less noisy. When teaching Chaucer's Book of the Duchess, I bring in my set of reproduction Lewis chessmen to make what can be an impenetrable metaphor in the poem, the Man in Black's repeated references to his lost love as a "fers" or chess queen, literally tangible. (The pieces are resin reproductions from Studio Ann Carlton.)  I also joke that perhaps one of the reasons why Chaucer's narrator may not understand the metaphor himself is that the chess queen (at left) isn't nearly as attractive as the description the Man in Black later gives of his lady, possessed of "Ryght white handes" and "Rounde brestes" (955-956). And then there's my cheap reproduction astrolabe, that medieval combination slide rule and star chart. A long discussion of the astrolabe is perhaps more suitable for a course on The Canterbury Tales, with its cornucopia of astrological references -- or, I suppose, if it exists anywhere, a course on Chaucer's own piece of technical writing The Treatise on the Astrolabe.  Nevertheless, many of the texts we're reading are illuminated by some hands-on time with this hallmark of medieval science and technology, even if only because many well-educated people still seem to think that "medieval science" is an oxymoron. Unfortunately, the characters on my own astrolabe are from the Arabic script, so it's difficult to do too much with it -- this is what you get from buying blindly on eBay, I suppose. Its mere presence in the classroom, however, can give students a new perspective on medieval learning and the medieval view of the universe. I also remind them that Chaunticleer, in addition to being a fantastic singer and a princely lion among roosters, has apparently internalized this complex device, and can make the most sophisticated astrological calculations on his own. The bird never ceases to impress!  Finally, nothing beats a discussion of pilgrim badges -- even in a course not covering the pilgrimage of The Canterbury Tales -- for opening up a conversation about the coexistence of medieval piety and medieval vulgarity. I pass around my own reproduction pilgrim badge, acquired on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Saint Thomas just a few years ago, during a quick trip to the cathedral gift shop. I then tell them that, for some reason, the modern caretakers of Canterbury Cathedral freely vend these pewter casts in several medieval shapes, but fail to stock the flying phalluses, vagabond vaginas, and other exotic badges that medieval sojourners proudly wore and that really must be seen to be believed. I think that genuine medieval badges are still quite possible to acquire, so some day I'll have to look into getting a really good one. Of course, after all this talk of props that bring old books to life and make them tangible, at the end of the day nothing is better than a book for achieving this same purpose. Circulating a facsimile of a manuscript is obviously indispensable for introducing the complexities of medieval textual culture to modern readers; I was lucky enough to obtain a copy of the Huntington Library's facsimile of the Ellesmere Chaucer for next to nothing, when the library was offering free copies with every new subscription to the Huntington Library Quarterly. This particular facsimile helpfully reproduces the dimensions of the pages, dwarfing the notoriously hefty Riverside Chaucer we use in class. In fact, the sheer difficulty of passing it around the classroom itself makes a point about the exclusivity of lavish productions like the Ellesmere and the possible conditions under which they might have been used by medieval readers. I think that about covers it for now, but I'm always looking for new ideas -- so I'm happy to hear about any other "props" that might be useful for teaching Chaucer or medieval literature in general! Of course, I haven't even begun to go into what sorts of unlikely images find their way into my daily PowerPoint presentations. Here's one, though, to leave you with, in my opinion the perfect image of the "whelp" or little puppy who serves as the unlikely oracular dream guide in The Book of the Duchess. Since the dreamer encounters the whelp after a royal hunt has concluded, I can only assume we're to imagine a miniature sighthound, just like my own 12-pound Italian greyhound: Many of my students, still new to Middle English, had missed the existence of the puppy entirely, but now that they can put a face on him, I don't think they'll soon forget him.

5 Comments

|

AuthorTimothy S. Miller, Ph.D. Archives

October 2016

CategoriesOther Sites |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed